Identity Theft

I don't believe "New Libertarian" should be an enforceable trademark. I don't believe in so-called "intellectual property." I do, however, believe in karma--and QandO has just earned a great big heapin' helpin' of the bad kind.

To dissolve, submerge, and cause to disappear the political or governmental system in the economic system by reducing, simplifying, decentralizing and suppressing, one after another, all the wheels of this great machine, which is called the Government or the State. --Proudhon, General Idea of the Revolution

The circumstances of the long emergency will require us to downscale and re-scale virtually everything we do and how we do it, from the kind of communities we physically inhabit to the way we grow our food to the way we work and trade the products of our work. Our lives will become profoundly and intensely local. Daily life will be far less about mobility and much more about staying where you are. Anything organized on the large scale, whether it is government or a corporate business enterprise such as Wal-Mart, will wither as the cheap energy props that support bigness fall away. The turbulence of the long emergency will produce a lot of economic losers, and many of these will be members of an angry and aggrieved former middle class.Although he jumped the gun a bit on peak oil, Warren Johnson made some very similar predictions during the energy crisis of the 1970s about the effects of a significant long-term increase in fuel prices. The outcome would be a decentralized economy of diversified production for local markets, much less demographic mobility, and more stable intermediate social institutions like extended families, neighborhoods, and communities.

Food production is going to be an enormous problem in the Long Emergency. As industrial agriculture fails due to a scarcity of oil- and gas-based inputs, we will certainly have to grow more of our food closer to where we live, and do it on a smaller scale. The American economy of the mid-twenty-first century may actually center on agriculture, not information, not high tech, not "services" like real estate sales or hawking cheeseburgers to tourists.

Farming. This is no doubt a startling, radical idea, and it raises extremely difficult questions about the reallocation of land and the nature of work. The relentless subdividing of land in the late twentieth century has destroyed the contiguity and integrity of the rural landscape in most places. The process of readjustment is apt to be disorderly and improvisational. Food production will necessarily be much more labor-intensive than it has been for decades. We can anticipate the reformation of a native-born American farm-laboring class. . .

Wal-Mart's "warehouse on wheels" won't be such a bargain in a non-cheap-oil economy. The national chain stores' 12,000-mile manufacturing supply lines could easily be interrupted by military contests over oil and by internal conflict in the nations that have been supplying us with ultra-cheap manufactured goods, because they, too, will be struggling with similar issues of energy famine and all the disorders that go with it.

As these things occur, America will have to make other arrangements for the manufacture, distribution and sale of ordinary goods. They will probably be made on a "cottage industry" basis rather than the factory system we once had, since the scale of available energy will be much lower -- and we are not going to replay the twentieth century. Tens of thousands of the common products we enjoy today, from paints to pharmaceuticals, are made out of oil. They will become increasingly scarce or unavailable. The selling of things will have to be reorganized at the local scale. It will have to be based on moving merchandise shorter distances. It is almost certain to result in higher costs for the things we buy and far fewer choices.

The automobile will be a diminished presence in our lives, to say the least. With gasoline in short supply, not to mention tax revenue, our roads will surely suffer. The interstate highway system is more delicate than the public realizes. If the "level of service" (as traffic engineers call it) is not maintained to the highest degree, problems multiply and escalate quickly. The system does not tolerate partial failure. The interstates are either in excellent condition, or they quickly fall apart.

America today has a railroad system that the Bulgarians would be ashamed of. Neither of the two major presidential candidates in 2004 mentioned railroads, but if we don't refurbish our rail system, then there may be no long-range travel or transport of goods at all a few decades from now. The commercial aviation industry, already on its knees financially, is likely to vanish. The sheer cost of maintaining gigantic airports may not justify the operation of a much-reduced air-travel fleet. Railroads are far more energy efficient than cars, trucks or airplanes, and they can be run on anything from wood to electricity. The rail-bed infrastructure is also far more economical to maintain than our highway network.

The successful regions in the twenty-first century will be the ones surrounded by viable farming hinterlands that can reconstitute locally sustainable economies on an armature of civic cohesion. Small towns and smaller cities have better prospects than the big cities, which will probably have to contract substantially. The process will be painful and tumultuous. In many American cities, such as Cleveland, Detroit and St. Louis, that process is already well advanced. Others have further to fall. New York and Chicago face extraordinary difficulties, being oversupplied with gigantic buildings out of scale with the reality of declining energy supplies. Their former agricultural hinterlands have long been paved over. They will be encysted in a surrounding fabric of necrotic suburbia that will only amplify and reinforce the cities' problems. Still, our cities occupy important sites. Some kind of urban entities will exist where they are in the future, but probably not the colossi of twentieth-century industrialism.

Taking into account the interests, of our presence in the region and development of democratic society in Kyrgyzstan, our primary goal —according to the earlier approved plans — is to increase pressure upon Akaev to make him resign ahead of schedule after the parliamentary elections Realizing the plan is of key importance as, we think, the present opposition is not strong enough to challenge the present authorities, though Akaev has claimed he is not going to prolong his terms of office. . .It mystifies me, by the way, that Bill O'Reilly insists on labelling George Soros as "far left."

With a view to providing favorable conditions and helping democratic opposition leaders come to power, our primary goal for the pre-elections period is to arouse mistrust to the authorities in force and Akaev’s incapacitated corruption regime, his pro-Russian orientation and illegal use of "an administrative resource" to rig elections. In this regard, the embassy’s Democratic commission, Soros Foundations, Eurasia Foundation in Bishkek in cooperation with USAID have been organizing politically active groups of voters in order to inspire riots against pro-president candidates.

We have set up and opened financing for an independent printing office — the Media Support center — and AKIpress news agency to interpret impartially the course of the elections and minimize state mass media propaganda impact. We also render financial support to promising non-governmental tele- and radio companies.Young's repeated references to Russian political influence confirm that American involvement in former Soviet Central Asia is just a strategic effort by Oceania to mop up the remnants of Eurasia, and to secure control of the Caspian oil basin.

According to public polls results, we can come to conclusion that only a minor part of the population— former USSR citizens — is satisfied with close cooperation with Russia. Young people are most likely oriented to the West. Therefore we consider it extremely important to popularize American way of life among them to diminish Russian influence. At least 45 national higher schools have their local Students in Action organizations, which we are planning to use properly during parliamentary and presidential elections. In our opinion, those additional funds ($5 mm) transferred by the Department of State to hold seminars in all leading Universities of Kyrgyzstan and organize training in western countries turned out insufficient.

In the view of the pit-election situation and effort to provide fair and democratic elections in the KR and retain our positions in mass media and contacts with the opposition leaders, I advise focusing on discrediting the present political regime, thus making Akaev and his followers responsible for the economic crisis. We should also take steps to spread information on probable restriction of political freedoms during the election campaign.

It is worthwhile compromising Akaev personally by disseminating data in the opposition mass media on his wife’s involvement in financial frauds and bribery at designation of officials. We also recommend spreading rumors about her probable plans to run for the presidency, etc. All these measures will help us form an image of an absolutely incapacitated president.

BENTONVILLE, Ark. - The U.S. House has approved a federal highway bill that includes $37 million for widening and extending the Bentonville street that provides the main access to the headquarters of Wal-Mart Stores Inc.For most of living memory, the central function of "our" elected representatives in northwest Arkansas has been to secure lots and lots of highway and airport pork for local corporate interests. For years, Third District Congressman John Paul Hammerschidt pursued federal highway funds with a single-mindedness that made Al "Senator Pothole" D'Amato look like a piker. I've written before in this blog about the Northwest Arkansas Council's (aka Cockroach Caucus) role in lying and manipulating its way into a taxpayer-funded regional airport. As long as I can remember, "our" local government has been a corrupt good ol' boy club serving the interests of Tyson, Wal-Mart, J.B. Hunt, and Jim Lindsey.

The company says it asked U.S. Rep. John Boozman, R-Ark., to help get federal money for the proposed project. U.S. Rep. Don Young, R-Alaska, added an amendment that put the work into the $284 billion bill, which is now before the Senate.

Wal-Mart spokesman Jay Allen said the company wants Eighth Street improved so the 10,000 workers at company headquarters will have an easier time getting to their jobs. In the time Wal-Mart’s headquarters has been at the site, the company has grown at a much greater rate than the street has been improved. Wal-Mart, as measured by sales, is the world’s largest company. Wal-Mart has 20,000 employees in the Bentonville area; about half of them work at the company’s headquarters.

“We have people living all over the area,” Allen said. “Infrastructure in northwest Arkansas is a big issue for us. This would represent another east-west corridor connected to the interstate, which would benefit everybody.”

The money in the transportation bill would widen the street and pay for connecting it to Interstate 540.

The central concern of any corporation is to make a profit. Anything which interferes with this profit making is eliminated. When this rule is applied to services, most particularly those 'natural monopolies' like electricity, water, rail transport, and 'human services' like hospitals, the results can be highly negative. Profitable, 'high traffic' areas are serviced, while less profitable are not. The wealthy get health care, the poor remain sick. In the old days, rural areas were not electrified because it cost too much. City districts with a lower population were not served with tram ways because it wasn't profitable.I confess to some reservations about this complaint. Ultimately, services should be paid for by those using them, and the price should reflect the cost of providing them. Of course, that's leaving aside near-term expedients for dealing with the unjust distribution of wealth, which results from government intervention on behalf of the privileged owning classes. But ideally, in an economy where labor keeps its full product and no economic exploitation takes place, people should not receive subsidized services that they aren't willing to pay for at the full cost. The cost of providing electricity and water to rural areas may be so high that, when the cost is internalized in price, people in those areas find wells, cisterns, solar and wind power, etc., to be more cost-effective.

Then, the corporation has a debt, the amount it had to pay to the city for the water works. To pay for this debt, employees are fired and rates increased. Since the industrial users are charged low rates, the people least able to afford the increases, small business and home owners, will pay the balk of increased costs. The consumer and the worker end up paying for the purchase.On the whole, I think the provision of below-cost services by government-owned utilities has been a powerful force for promoting our dependence on "hard energy" distributed through centralized grids, and impeding the adoption of decentralized forms of appropriate technology or intermediate technology.

Rail, public transit, electricity generation, water and sewage treatment represent hundreds of billions of dollars of tax payer money invested over the last 90 years. To this figure must be added lands expropriated or given as gifts to build dams and railroads. Privatization hands all this wealth - that we tax payers in theory own - to corporations at a cut rate, for if they were sold at their true cost, no one would buy them.Amen! This was pretty much the finding of a recent study of water "privatization." In many cases, the government had to spend even more money upgrading facilities, before "private" corporations would find it worthwhile to purchase them. In effect, the taxpayers have paid the corporations to take public assets off their hands.

The policy of deregulation and privatization was never designed to improve services, it was designed to loot.

Instead of encouraging investment, privatisation has left governments offering increased concessions to entice investors to acquire their assets– often to meet the requirements of donors. For example, between 1991 and 1998 the Brazilian Government made some US$85 billion through the sale of state run enterprises. However, over the same period, it spent US$87 billion ‘preparing’ the companies for privatisation.Larry concludes his post with a call for expropriating "privatized" services (without compensation), and placing them under a system of cooperative governance with day-to-day management carried out by the workforce's representatives, and strategic control divided between representatives of the labor force, consumers, and community.

Rather than being a major source of finance, private contractors are committing little of their own capital and are instead looking to municipalities, central government or donor governments/institutions to provide the money....

In fact, in many cases foreign companies are relying on the donor community to bail them out when they get it wrong.

Doctors, trade unions, Medicins sans frontieres are all opposed. These projects result from bureaucratic empire-building, and are not derived from any real need.Hospitals, he writes, are an ideal candidate for mutualization:

The mega-hospitals will centralize the power of the health care bureaucracy even more than it already is. And as someone who works in health care, I can tell you that they have enough trouble running the system now.

Ironically, hospitals would be an ideal place for introducing worker-self management. They are not owned by a corporation, and supposedly belong to the community. They have a highly educated staff. A council composed of nurses, doctors, technical, trade and support staff, elected by mass meetings of the groups concerned would be the best form of management. For sure such a group would not come up with a crack pot idea like a mega hospital!

It is asserted that for British Columbia, the "co-op" or "co-operative model" of development, while is thusfar underutilized, is the best institutional vehicle to bring about such an economic model of development.

A model of development predicated on co-operatives could maximize democratic control of development by local citizens who would be the voting members of the co-op. It could mobilize the savings of citizens and perhaps even union pension funds.

You show me a polluter and I’ll show you a subsidy. I’ll show you a fat cat using political clout to escape the discipline of the free market and load his production costs onto the backs of the public.

The fact is, free-market capitalism is the best thing that could happen to our environment, our economy, our country. Simply put, true free-market capitalism, in which businesses pay all the costs of bringing their products to market, is the most efficient and democratic way of distributing the goods of the land – and the surest way to eliminate pollution. Free markets, when allowed to function, properly value raw materials and encourage producers to eliminate waste – pollution – by reducing, reusing, and recycling.

In a real-market economy, when you make yourself rich, you enrich your community.

The truth is, I don’t even think of myself as an environmentalist anymore. I consider myself a free-marketeer.

Corporate capitalists don’t want free markets, they want dependable profits, and their surest route is to crush the competition by controlling the government.

Let’s not forget that we taxpayers give away $65 billion every year in subsidies to big oil, and more than $35 billion a year in subsidies to western welfare cowboys. Those subsidies helped create the billionaires who financed the right-wing revolution on Capitol Hill and put George W. Bush in the White House.

There is a great deal of evidence that almost all organizational structures tend to produce false images in the decision-maker, and that the larger and more authoritarian the organization, the better the chance that its top decision-makers will be operating in purely imaginary worlds.

when complexity and interdependence have reached such unmanageable proportions... the system generates transaction costs faster than it does production...."

Right-libertarians sometimes wish to weaken the state without simultaneously weakening other institutions that have grown fat on the state.

Why do the greater part of cooperatives behave in much the same way as other firms in terms of management and in terms of the links they develop, or don't develop, in their communities?

I've concluded that the essense of the challenge activists for economic democracy face is that we can never negotiate a cooperative commonwealth based on orthodox economic terms.

The prairie populists of Canada and USAmerica once had a unique opportunity for a breakthrough past the restraints of the orthodox economics of the early twentieth century.

Social democratic Fabianism, which would be an early adopter of Keynesian policy prescriptions, came to dominate socialist thought and shape the limits of a socialist agenda. It also displaced guild socialism and its historic project of building a decentralized and non-statist social economy. Fabianism more-or-less adopted the conventional wisdom of orthodox economics.

Populists and socialists in USAmerica and Canada squandered their opportunity to build the cooperative commonwealth in North America when the larger part of the movement gave way to a Fabian form of social democracy.

In brief, ...the inevitability of centralism will be self-proving. A system destroys its competitors by pre-empting the means and channels, and then proves that it is the only conceivable mode of operating.

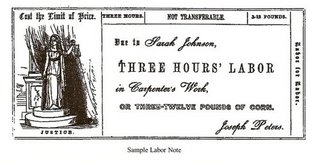

Along these lines, I want to sketch an updated version of mutual banking, complete with e-money transfer capability via the Internet. As I see it, a mutual bank should grow from a collectively owned and operated barter association that is responsive to the participatory-democratic assembly of a radical urban community. Here's a possible scenario:

The new economic system -- not yet self-sufficient but increasingly so -- is born when the community barter association begins issuing an alternative currency accepted as money by all businesses within the system. For reasons discussed below, this "currency" does not at first take the form of tangible monetary tokens (i.e. coins or bills), but is circulated entirely through transactions involving the use of barter-cards, personal checks, and "e-money" transfers via modem/Internet.

Since it doesn't charge interest -- the source of regular banks' profits -- and since its purpose is to provide economic assistance to the community, it may be possible to charter this new financial institution as a nonprofit charitable organization. In order to get non-profit status, however, it is essential that mutual-credit organizations not be officially described as "banks" "thrifts," "savings and loans," "credit unions," etc., which would make them subject to the charter laws governing such institutions. For convenience I'll refer to an anarchist zero-interest credit-issuer as a "mutual barter clearinghouse" (or just "clearinghouse" for short). Other semantic expedients regarding the official description of its operations may also be necessary in dealing with the State.

The clearinghouse has a twofold mandate: first, to extend interest-free credit to members; second, to manage the circulation of credit-money within the system, charging only a small service fee (probably one percent or less) which covers its costs of operation. Such costs would include the making of plastic barter cards, printing personal checks, keeping track of transactions, paying its workers, insuring itself against losses from uncollectible debts, and so forth.

The clearinghouse is organized and functions as follows. Members of the original barter association are invited to become subscriber-members of the mutual bank by pledging a certain amount of property as "collateral" (referred to by some other term -- perhaps "pledge" is good enough). On the basis of this pledge, an account is opened for the new member and credited with a sum of mutual dollars equivalent to some fraction of the assessed value of the property pledged. [2] The new member agrees to repay this amount plus the cost-covering service fee by a certain date. The mutual dollars in the new account may then be transferred through the clearinghouse by using a barter card, by writing a personal check, or by sending e-money via modem to the accounts of other members, who have agreed to receive mutual money in payment for all debts.

The opening of this sort of account is, of course, the same as taking out of a "loan" in the sense that a commercial bank "lends" by extending credit to a borrower in return for a signed note pledging a certain amount of property as security. It's like fractional-reserve banking in this respect. The crucial difference, however, is that the clearinghouse does not purport to be "lending" a sum of money that it *already has*, as is fraudulently claimed, with much hand-waving and doubletalk, by commercial banks. (Hence the creation of mutual credit does not have to be officially described as "making a loan.") Instead it honestly admits that it is creating new money in the form of credit, but charging no interest for doing so. New accounts can also be opened simply telling the clearinghouse that one wants an account and then arranging with other people who already have balances to transfer mutual money into one's new account. --

What is the reason that so many bottom-up ideas and innovations never make it into the commercial marketplace? I'm not a believer in conspiracy theories that corporations deliberately buy up and suppress more durable inventions to keep them from cannibalizing their market. I think it's more likely that people with good ideas are just disconnected from those with the skills and resources needed to implement those ideas. And vice versa -- those with commercialization skills and resources are rewarded by the market (and by shareholders) for not fixing what ain't broke, for not changing what they're doing until and unless they have to.

So on the one hand we have an astonishing and unprecedented flood of good ideas, made possible by the democratization of knowledge (the Internet etc.), and on the other hand we have this incredible inertia by those who could make those ideas reality, change everything.

Although Travis was a patriotic Kentucky boy, the U.S. government thought any song complaining about hard work and hopeless debt was subversive. The song got Travis branded a “communist sympathizer” (a dangerous label in those days). A Capitol record exec who was a Chicago DJ in the late 40s remembers an FBI agent coming to the station and advising him not to play “Sixteen Tons.”

In a healthy human community, jobs are neither necessary nor desirable. Productive work is necessary – for economic, social, and even spiritual reasons. Free markets are also an amazing thing, almost magical in their ability to satisfy billions of diverse needs. Entrepreneurship? Great! But jobs – going off on a fixed schedule to perform fixed functions for somebody else day after day at a wage – aren't good for body, soul, family, or society.

Intuitively, wordlessly, people knew it in 1955. They knew it in 1946. They really knew it when Ned Ludd and friends were smashing the machines of the early Industrial Revolution (though the Luddites may not have understood exactly why they needed to do what they did).

Jobs suck. Corporate employment sucks. A life crammed into 9-to-5 boxes sucks. Gray cubicles are nothing but an update on William Blake's “dark satanic mills.” Granted, the cubicles are more bright and airy; but they''re different in degree rather than in kind from the mills of the Industrial Revolution. Both cubicles and dark mills signify working on other people's terms, for other people's goals, at other people's sufferance. Neither type of work usually results in us owning the fruits of our labors or having the satisfaction of creating something from start to finish with our own hands. Neither allows us to work at our own pace, or the pace of the seasons. Neither allows us access to our families, friends, or communities when we need them or they need us. Both isolate work from every other part of our life....

We've made wage-slavery so much a part of our culture that it probably doesn't even occur to most people that there's something unnatural about separating work from the rest of our lives. Or about spending our entire working lives producing things in which we can often take only minimal personal pride – or no pride at all.

Our natural resources, while much depleted, are still great; our population is very thin, running something like twenty or twenty-five to the square mile; and some millions of this population are at the moment "unemployed," and likely to remain so because no one will or can "give them work." The point is not that men generally submit to this state of things, or that they accept it as inevitable, but that they see nothing irregular or anomalous about it because of their fixed idea that work is something to be given.

Although computer-based “knowledge work” hasn't enabled millions of us to leave the corporate world and work at home (as, again, it was supposed to), that's more a problem of corporate power psychology than of technology. Our bosses fear to “let” us work permanently at home; after all, we might take 20-minute coffee breaks, instead of 10!

And we can begin to consider: What types of technology let us live more independently, and what types of independence still enable us to take advantage of life-enhancing technologies while keeping ourselves out of the life-degrading job trap?

Take a job and you've sold part of yourself to a master. You've cut yourself off from the real fruits of your own efforts.

When you own your own work, you own your own life. It's a goal worthy of a lot of sacrifice. And a lot of deep thought.

Like Merle Travis and Ned Ludd, anybody who begins to come up with a serious plan that starts cutting the underpinnings from the state-corporate power structure can expect to be treated as Public Enemy Number One.

government and its heavily favored and subsidized corporations and financial markets....

A Republican friend of mine, who supported the drilling, asked why doesn't the government just auction off the property rights? That way if the environmentalists want to stop the drilling, they can try to buy it, and is the oil companies want to drill, they'll actually have to pay for it.

It's a genius idea, and one I'd advocate for much of the public lands system.

The United States Treasury will likely never see the drilling revenues presupposed by President Bush's 2006 budget. The budgetary estimates drastically exaggerate the price per leased acre, in some cases expecting "between 66 and 120 times the historic average." Waning industry interest in the area is also a serious factor and one of President Bush's own advisors stated, "If the government gave [the oil companies] the leases for free, they wouldn't take them."

House Majority Leader Tom DeLay (R-TX) spoke about the "symbolism involved in opening up the refuge to drilling" as well as the precedent the move will set. DeLay's comments reveal that drilling in ANWR is "a domino game that will lead to drilling in the Rocky Mountains, off the California coast and in the Gulf of Mexico." Watch out when the moratorium on eastern Gulf drilling expires in 2007.

This September, returning residents of East Quad were dismayed to find that the dorm’s Benzinger Library had sold off its collection of hundreds of CDs and DVDs, converting it from a circulating library into a so-called Community Learning Center. Outraged by the decision to unload the library’s collection and fed up with the general lack of transparency on the part of University Housing, several students have banded together to form the Benzinger Library Cooperative to rebuild from scratch the once-mighty collection of media free from the meddling influence of University administrators....

The BLC’s dealings with University administration have been less than successful. University Housing is trying to maintain control over the library without providing any material assistance to the students’ efforts. Atkinson describes Director of Community Learning Centers David Pimentel as “a bureaucrat of the most aggravating sort” for refusing to relax his iron grip on the Benz and relinquish control to students. But in the end, fruitless negotiations will have no impact on future BLC operations. “Generally, we’re pretty fearless,” boasts Atkinson. “We’re running a library, and they can suck it.”...

Another example of unnecessary Housing meddling in student affairs is the recent efforts of officials to eradicate any and all remnants of originality from East Quad’s basement café, the Halfway Inn (known colloquially as the Halfass). Up until two years ago, students were encouraged to decorate the Halfass however they saw fit. Sadly, the enlightened minds in University Housing decided that it would be in the students’ best interest to replace the vibrant murals with a bland shade of white paint and destroy the subdued ambience by installing soul-suckingly drab fluorescent lighting. After enacting these changes and facing the inevitable torrent of criticism, Housing benevolently offered to hold a mural-making contest in which Housing administrators would select a student to paint a pre-approved mural. An alternative proposed by students is to hold a mural day in which all residents are encouraged to just show up and start painting. According to Atkinson, Housing is not thrilled with this idea, as “they are dedicated to making East Quad one big corporate break room.”

Bush and other libertarian-style thinkers that have gained prominence in Washington, D.C. in recent decades champion markets in the extreme. They are enthusiasts of laissez faire who oppose strong governmental intervention in the affairs of individuals and businesses. Libertarians prefer to reduce government’s activities to a few essential services such as defending the public from foreign threats and protecting citizens from criminals. They seek the privatization of state-run programs (such as Social Security) and massive tax cuts. Often they advance their goal of limited government by squeezing the budgets of social programs.

So what, in general, is exploitation? Broadly, let’s say that Ann exploits Betty when Ann takes unfair advantage of Betty. Harmful exploitation occurs when A unfairly benefits from B at a net expense to B. In contrast, mutually advantageous exploitation occurs when A takes unfair advantage of B, but there is also a net benefit to B. In addition, we can distinguish consensual and nonconsensual forms of exploitation. Let’s say a transaction is consensual when consent is given by a competent adult in the absence of direct coercion or fraud.

Now it would seem uncontroversial that nonconsensual harmful exploitation is wrong. If I’m a business owner and Lefty and Knuckles come by and inform me that something very bad could happen to me if I don’t pay $500 a month to their “protection” organization, then, if I pay up, they are benefiting at my expense against my will. This is a clear case of exploitation. Interestingly, a more widespread form of exploitation of this kind tends to go without much comment. That is, when the government takes a portion of my paycheck each month against my will and informs me that failure to pay up could result in something very bad happening to me, it seems that this too is a form of exploitation. I don’t want their services any more than I want the “protection” services of Lefty and Knuckles, but they benefit at my expense anyway.

At any rate, the interesting cases are those that purportedly involve mutually advantageous exploitation. These are cases where A unfairly benefits from B, but B also benefits. But benefits relative to what? It seems we should say that B benefits relative to a no-transaction baseline. And at this point the libertarian has had enough . . .

“What is all this crap about exploitation? B gives valid consent to A and B benefits from the transaction. Where’s the unfairness here? Is it unfair because B would prefer more, or because s/he thinks s/he deserves more?”....

Take a case in which a person in the Third World takes a job in what we in the First World would term a sweatshop. She voluntarily consents to work there and she benefits on the whole because the wages are significantly higher than anything else she could get in the local labor market. Could she be exploited? Let’s add some background details.

The IMF and the government of her country have implemented “structural adjustment” (i.e., crony capitalism in new dress) and as part of this the land that her family has farmed for generations has been sold out from under them to a politically connected corporation. And since the property rights of peasants are not protected in this corrupt legal framework, she has no real choice but to move to the slums of a large city and seek paid employment. The labor market is by no means free (unions are highly legally restricted and labor organizers are regularly hurt or killed).

The factory she works for pays a higher wage because of greater capital investment, and hence greater worker productivity. So while she benefits from employment at the factory relative to both a no-transaction baseline and to her other employment options, she is still arguably exploited by the employer because the employer is able to take advantage of her artificially low bargaining position.

We have no right to ban voluntary, mutually beneficial transactions even if they are exploitative. To interfere in this transaction is to interfere with the self-determination and rights of free association and contract of the people involved. Moreover, if this exploitative transaction is currently the best option for our subject, then taking away that option will just make her worse off. Being exploited is bad, but having one’s freedom and autonomy violated is worse....

So while leftists are right to insist that even voluntary transactions can be exploitative, libertarians are right to insist that even exploitative voluntary transactions should not be subject to state interference.

....[T]he appropriate response to globalization is not to increase restrictions on trade, but to fight those conditions that give some the ability to take unfair advantage of others....

Individualist Anarchism sees the exploitation of certain groups or classes as the visible symptom of a deeper problem whose root cause is coercive monopoly. The individualist does not sanction the use of force to fight the symptom, but only to fight the coercive root cause itself. Non-coercive monopolies are to be opposed only through peaceful and cooperative means, such as innovation and education.

Ferguson makes it sound as if colonial authorities stuck around basically because they were readying their wards for self-rule. And it is easy to find lengthy disquisitions from Macaulay, Churchill, Smuts, and the like to this effect. Indeed, whenever he feels compelled to present evidence for his view, Ferguson quotes from them, rather than referring to the historical record. We very quickly encounter Churchill enunciating the general principle behind British colonialism: “to reclaim from barbarism fertile regions and large populations . . . to give peace to warring tribes” and so on. Soon thereafter, Macaulay is drafted to the campaign, declaring, “never will I attempt to avert or to retard” Indian self-rule, which, when it comes, “will be the proudest day in Indian history.”

Once demands for self-rule emerged in Asia and Africa, authorities responded with violence. From the early decades of the 20th century, progress toward self-rule proceeded in lockstep with the strength of the movements demanding it. But Ferguson makes no reference at all to either the massive independence movements that finally rid the world of British colonialism, or to the quality of the British response to them. But even the briefest consideration of these phenomena undermines the notion that the colonizers were educating the “natives” in the ways of self-rule.

When confronted with anti-colonial mobilizations, the British would make political concessions on the one hand, while taking steps to divide the opposition on the other. In India, the divide-and-rule strategy exploited existing religious divisions by communalizing the vote. From the passage of the Minto-Morley reforms in 1909, the advancement of the independence movement also brought in train a deepening of Hindu–Muslim tensions, as electoral mobilization—limited though the elections were—pitted communities against each other.

For the British, the central dilemma, as Mahmood Mamdani has reminded us, was to figure out how “a tiny and foreign minority [can] rule over an indigenous majority.” The natural strategy was to rely heavily on local elites—tribal chiefs, landlords, and especially the priestly strata—and thereby reinforce the symbolic, cultural, and legal traditions that sanctioned rule by these elites. In India, it meant using local caste and religious divisions and giving them a salience that they had never enjoyed before. In Africa, this entailed a splintering of civil law and political rights on ethnic and tribal criteria, relying ever more strongly on the despotic rule of chiefs and hardening indigenous linguistic and cultural divisions.

Consider the process of hardening in the case of equatorial Africa, Ferguson’s preferred target for re-colonization. Chiefs were certainly in place before the British arrival. But in pre-colonial times, chiefly power was circumscribed and balanced by both lateral checks—consisting of kinsmen, administrative functionaries, and clan bodies—and vertical checks, consisting of village councils and public assemblies. These institutions did not by any means democratize pre-colonial polities; but they did impose real social constraints on chiefly rule and thus imbue it with a degree of legitimacy. The chief was the paramount power, but his power was constantly negotiated with peers and subordinates.

Colonial rule either severely weakened or simply dissolved these social constraints. The colonial authorities needed to have clearly identifiable nodes of power through which they could exercise their rule, and these local functionaries could not be accountable to anyone but the colonizer. So the clan bodies, village councils, and public assemblies were either dissolved or made toothless against the chiefs. What remained was a stern, vertical line of authority from the colonial office, though the district administrator, to the chief—all according to London’s desires. Locally, the indigenous state structure was turned into what Mamdani has appropriately called a decentralized despotism, as chiefs were endowed with unprecedented power.

Throughout the colonies, it became standard practice to declare all "uncultivated" land to be the property of the colonial administration. At a stroke, local communities were denied legal title to lands they had traditionally set aside as fallow and to the forests, grazing lands and streams they relied upon for hunting, gathering, fishing and herding.

Where, as was frequently the case, the colonial authorities found that the lands they sought to exploit were already "cultivated", the problem was remedied by restricting the indigenous population to tracts of low quality land deemed unsuitable for European settlement. In Kenya, such "reserves" were "structured to allow the Europeans, who accounted for less than one per cent of the population, to have full access to the agriculturally rich uplands that constituted 20 per cent of the country. In Southern Rhodesia, white colonists, who constituted just five per cent of the population, became the new owners of two-thirds of the land.... Once secured, the commons appropriated by the colonial administration were typically leased out to commercial concerns for plantations, mining and logging, or sold to white settlers.

International trade is essential to prosperity. But given a high degree of disorder, large scale trade cannot occur, or at least will be greatly impeded. Throughout history, empires have been the main means by which order has been preserved and trade promoted: "By creating order over a large economic space, empires have inevitably generated [Adam] Smithian intensive growth" (p. 43).

Applied to the present, Lal's argument becomes this: International trade requires an imperial power. Only the United States has the resources to maintain hegemonic control. Therefore, the United States ought exercise imperial power.

Good empires are what Michael Oakeshott calls civil associations. They are content to preserve order. The bad empires are, in Oakeshott's terms, enterprise associations.

Someone needs write a new Black Book of Capitalist Imperialism to put next to the Black Book of Communism.

The libertarian Richard Epstein, following through on individualist intuitions about justice, has argued in favor of replacing our negligence system of torts with a system of strict liability ("A Theory of Strict Liability," 2 Journal of Legal Studies 151 (1973)). Such a system would ensure that whenever one person caused damage to another, they'd have to compensate them for it. Long before we reached this point, I'd be joining the critics of the tort system in crying "crisis!" The problem wouldn't be frivolous lawsuits. It's that when negative externalities are systematic, it's grossly inefficient to deal with them on a case-by-case basis, as the tort system does. The costs of litigation are too high, not in the amounts of judgments, but in lost production opportunities, as the valuable time of defendants and plaintiffs gets sopped up in lawsuits. That's why I prefer alternatives to litigation, such as regulations for worker safety and pollution, workers' compensation, and no-fault auto insurance, to cover systematic costs imposed on people by our advanced capitalist system of production. Excessive reliance on Individualized solutions puts too much sand in the gears of capitalist production.

Inside the movement, free-marketeers have conflated laissez faire with "capitalism," thanks in no small part to Ayn Rand's infatuation with the term. Outside the movement, opponents of "crony capitalism" have assumed, not without some justification (if you throw a word around without knowing its meaning, you get what you deserve), that libertarians endorse the crony capitalism which characterizes most industrialized economies today.

It wasn't always that way. As a matter of fact, it still isn't that way. Take a closer look at the libertarian mosaic and other colors begin to bleed through the chartreuse. Long ignored or denied by the "mainstream" of the libertarian movement, the colors of anti-capitalist free market ideas have been there all along. Some of these ideas may be key to reforming the Democratic Party in a libertarian direction.

One of the more vexing problems to which libertarianism addresses itself -- or, more frequently, cowers from addressing itself -- is the problem of land, whether or not it can be owned and if so, how.

Fortunately, fundamental honesty often conforms with, rather than conflicting with, political expediency. Consideration of Paine's "ground rent" idea, or some variant thereof (such as the one popularized by Henry George in the late 19th century, often called the "Single Tax"), may be the key to real tax reform which moves government away from punishing labor, creation and innovation and toward collecting legitimate fees for the use of common resources held in trust.

Locke's idea worked ... as long as there was no scarcity of land relative to those who wished to use it, and as long as no supervening entity, such as government, claimed the authority to decide between claimants in that environment of scarcity.

"We were in pretty shitty private accommodation and we thought, 'Why not play the system?'" recalls biology degree drop-out Martin Newman, whose fascination with radical ideals of bands such as The Clash, The Specials and New Model Army belied a determination to work the system, rather than fight the class war. "We decided it was cheaper to buy a place rather than keep on renting," Newman says. "And Mrs Thatcher, after all, was encouraging people to make money, so we hatched this plan to organise and achieve, rather than bringing down capitalism first."

But in solving their own accommodation crisis, the young idealists - "green, practical anarchists", according to Newman - soon discovered they could help others who were living rough. They learned a few tricks of the building trade, taught themselves rudimentary joinery, plastering and plumbing, and used their first property as collateral for another house. Then they acquired another. Giroscope workers' cooperative was born....

Remarkably, the cooperative is still in business, and the future should look rosy. Two of the founders - Newman, the DIY all-rounder, and Michael Shutt, the plumbing specialist, both aged 40 and much wiser - provide a lead for younger partners such as John Wood, the 25-year-old administrator, and Andy Holden, 36, another jack-of-all-trades. They pay themselves about half the average national wage - less than £10,000 per annum - and now manage 32 houses and flats, while letting a corner shop and part of their solar-powered headquarters to an organic food cooperative.

Unlike other landlords, Giroscope demands no deposits from prospective tenants - although references are needed - and the weekly rent, which varies between £45 and £70, is modest by today's standards. "There's always a big demand for our places," says Shutt.

As a result, Newman and his colleagues fear that their enterprise is now on the line. If houses are compulsorily purchased, as a prelude to demolition, they say that compensation on offer will be insufficient to buy alternative properties - because, ironically, prices in the area are now the highest for 20 years.

....the Office of Labor-Management Standards, which investigates and audits labor unions, is thriving. This year 48 new positions and a 15 percent budget increase were granted to the office, and since Bush has been in office they have benefited from 94 new positions and a 60 percent overall increase in the budget. Last year the Labor Department began imposing extraordinarily detailed financial reporting requirements for unions and related institutions, like credit unions. Although the AFL-CIO is still pursuing a legal challenge to the rules, the new requirements—which far exceed those placed on corporations—have already eaten up dues that could have been spent on providing members with services. In addition, the reports expose details about union strategies that could be helpful to employers and political opponents.

“The real motivation was to saddle unions with expensive and time-consuming requirements to harass them and to provide the kind of ammunition that a Right to Work Committee researcher or Republican staffer would find very useful, but union members would find not useful at all,” says AFL-CIO General Counsel Deborah Greenfield. “I don’t think it’s an accident that the head of the agency within the Department of Labor who came up with the rule, Don Todd, was head of research for the Republican National Committee.”

Increasingly, unions organize, as they did many years ago, by getting employers to recognize the union when a third party verifies that a majority of workers have signed union cards—a practice known as “card check.” The board has now signaled that it may make such recognition illegal or at least permit union decertification elections immediately, rather than after at least one year under current rules.

In other cases, the board appears determined to narrow the scope of agreements that unions and management can reach before majority worker support is established. In February a regional NLRB director challenged an agreement between the Steelworkers and a manufacturing investment company to establish management neutrality during an organizing drive. Hiatt and Becker warn that if the board decides against neutrality agreements and majority card recognition, it may “place union representation effectively beyond the reach of most American workers.”

you can have a capitalism without capitalists. You can have all the profit seeking behaviours, without the personal gains for any real sensuous human being.